Licensing, Ownership & DOIs

Learning objective:

- Understanding ethical and legal aspect of giving credits and attributions

- Learning about existing open source licenses and Digital Object Identifier

Disclaimer: the contents of this lesson are for educational purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be used as such.

Introduction

After deepening your understanding of the reasons to use open-software in the context of open-science, we here address the first considerations when using an open software tool in your research. First and foremost, if you are going to be building your own code on prior work you need to choose a software that is open, i.e., that you are allowed to use, modify and redistribute. As a developer, you also need to ensure that you are sharing a product that is open - and thus, usable - to others. This is presented on the section Licenses.

Then, we present how you get credit for your work, and how you give credit to others’ work. This is the content of the section Attribution and citation.

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to: Choose and abide by appropriate usage and referencing standards of open-software.

Licenses

A software license is a legal document that grants users particular rights to the use of a certain software. This license can take many forms, but in many cases they outline contractual obligations (if any exist) between the company/software developer behind the software and the end user, what the user can do with the software, who the user can distribute the software to (if any such distribution rights exist) and the length of time the user has the right to use the software.

A user cannot (technically and ethically), use a software without a license! A user can reach out to the developer/owner to ask for permission, and go ahead if the owner/developer furnishes written permission. But, if you share your software without a license, no one can use it without your written permission!

Types of licenses

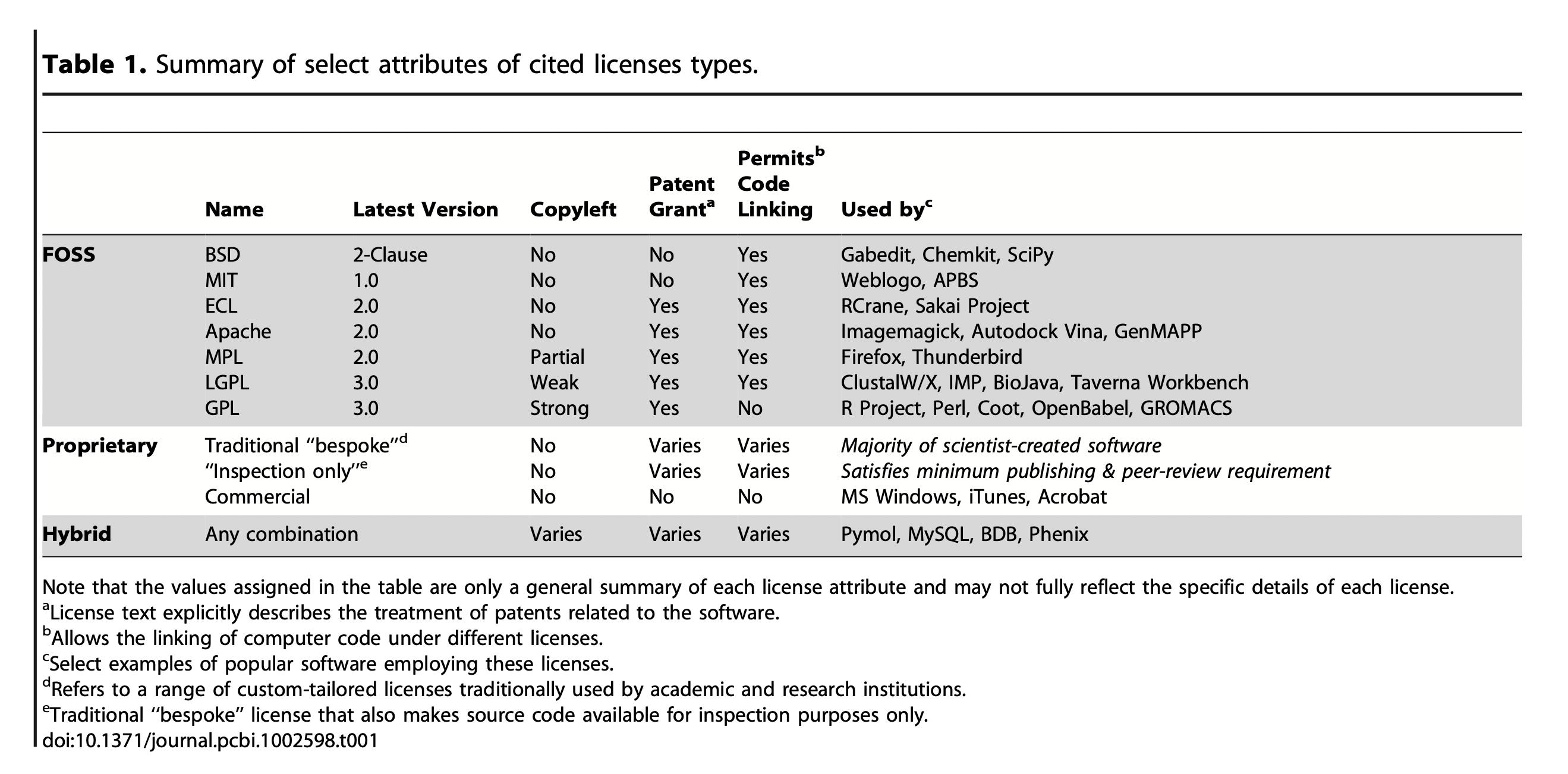

A license can fall under several categories. License types have general definitions of what can be done with the software. By picking a type of license, or by understanding what type the license of a software you’re considering using is, you’ll be able to navigate the license process more quickly than reading each license individually and interpreting the permissions. An overview of types of licenses is given in the table below1:

| Public domain license | Lesser general domain license | Permissive | Copyleft | Proprietary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anyone can use or modify the software. | Can link to open source libraries and code can be licensed under any license type. | Has some requirements for distribution and modification. | Licensed code can be distributed or modified if all the code involved is licensed under the same license. | Software cannot be copied, modified or distributed |

Summary of selected attributes of licenses types 2:

Some of the common licenses used in open software are:

- MIT license

- Apache License 2.0

- Mozilla Public License 2.0

- BSD 3-Clause “New” license

- GNU General Public License (GPL)

- Common Development and Distribution License

For more information on different types of licenses please refer to the (Open Source Initiative OSI).

How to choose a license

There are a number of steps that have to be made before choosing a particular license. Arguably one of the first decisions to be made is based upon whether you intend to use the code for commercial purposes or not, or at least foresee it as a possibility in the future. Some licenses are more favorable for commercial purposes than others, such as the General Public License, version 2.

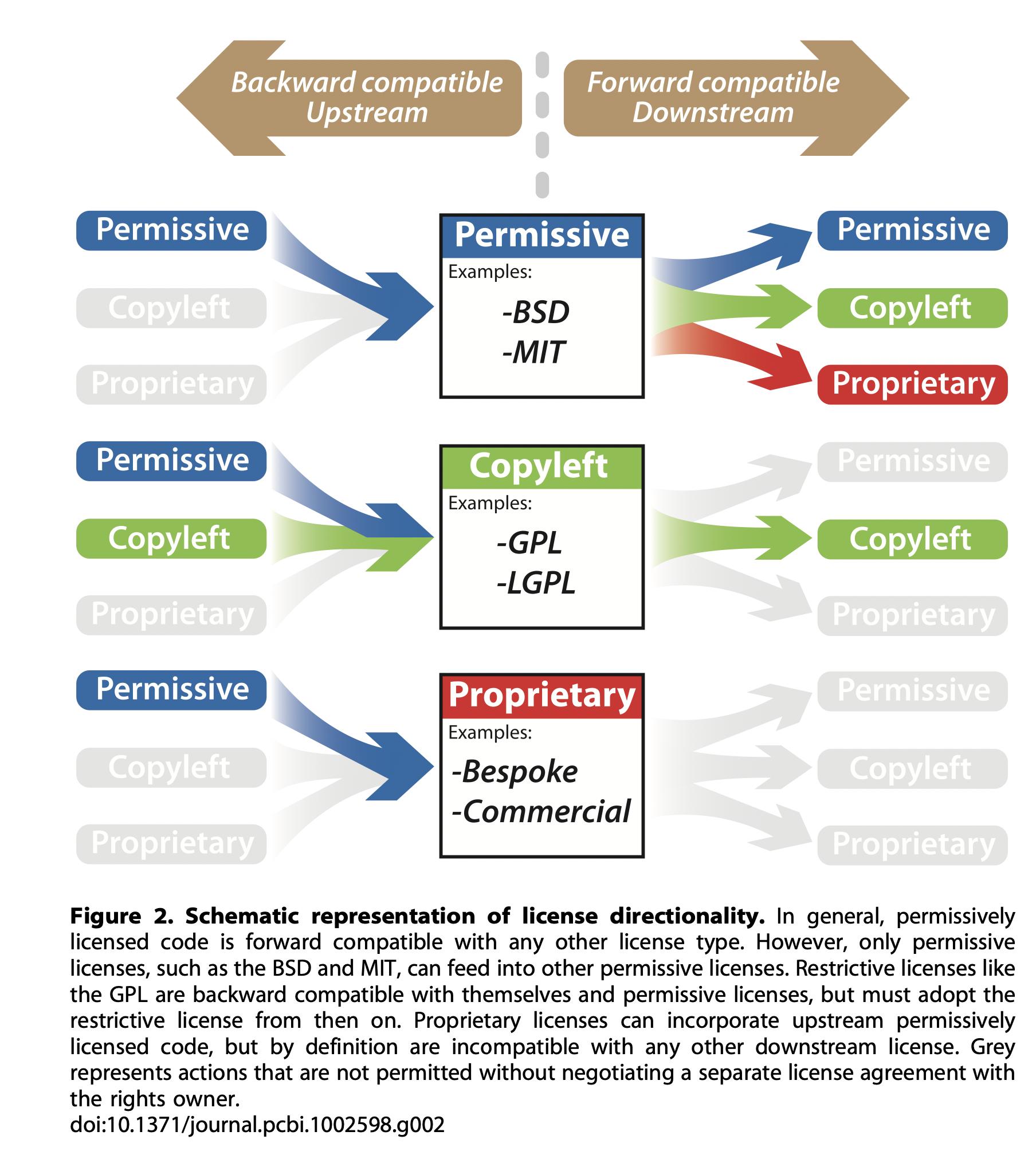

The next decision that has to be made is relating to the issue of distribution. When using other software as a dependency, you should always be wary of their licenses. Some licenses enforce certain types of licenses upon redistribution. The GNU GPL, for instance, is incompatible with proprietary licenses, because it requires the combined work to be licensed under the GPL, with no additional restrictions allowed. Having a part of the work under a proprietary license is such an additional restriction, so you cannot distribute such a combination (unless the copyright owner of the GPL code gives special permission). 3

For licensing open software, it is always good practice to consult with the Open Source Initiative (OSI) website. They provide a list of approved licenses that guides you through this process. Remember that a first step is always to consult with your institution (if applicable). You should ensure that you are complying with any applicable local laws and any policies set by your employer and/or funding entity.

Additional Resources

Attribution and citation [^Katz]45

Both when choosing a license and publishing your software for future citation, a decision has to be made in relation to the issue of attribution, i.e., crediting a person or group of people or other entity with a particular action in relation to the software. This can be thought of as the software/code equivalent to authorship on an academic paper. It is important to consider this to avoid accusations of plagiarism or copyright infringement. There is a short discussion in the final lesson in this module regarding ethical considerations on how contributions can be considered for authorship/attribution/ownership.

When deciding to cite a software or code that was used in your research you can start with the question: is this research software? Research software includes source code files, algorithms, scripts, computational workflows, and executables that were created during the research process or for a research purpose. Software components (e.g., operating systems, libraries, dependencies, packages, scripts, etc.) that are used for research but were not created during or with a clear research intent should be not be cited (e.g. Microsoft Word, Linux, Python –the language itself; specific packages might be citable in this context). This differentiation may vary between disciplines. Some examples of research software that would be cited are E3SM, SciML, and Stock Synthesis.

The majority of open source software licenses require some degree of attribution, and a small minority (such as the 0BSD) do not. The license will also dictate where the attribution must be displayed - some licenses will require the user to include attribution in a dedicated file such as the software license agreement.

Digital Object Identifier (DOI)

By having a persistent identifier, a software version can be cited. A digital object identifier (DOI) is a persistent identifier or handle used to uniquely identify various objects. It is provided and standardized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In contrast to dynamic web addresses such as URLs, DOIs are static, i.e., do not change over the life of a document, and point to the location of the document on the internet. You can get a DOI for your own software/code by adding it to a preservation repository.

Just as we publish scientific findings in writing in journals to ensure its preservation over time, its supplementary material, e.g., source code and produced data, should also be stored in a permanent location. We call these preservation repositories. Some of these repositories are general-purpose such are Zenodo and Figshare, and some are more research field-oriented such as Hydroshare.

It is important to keep in mind that a DOI refers to a static version of your code and so, you’ll need to get a new DOI for each version you release and want cited. By using the same repository each time you need a DOI for a new version, you can be sure that when a user looks for your DOI they are directed towards the most recent version.

Citing code without a DOI

As a user, if you’d like to cite a software that does not have a DOI you can use Software Heritage to create a SWH-ID which is also a citable persistent identifier, but can be created for codes that are not your own. This should only be done after ensuring a DOI is not available otherwise there can be multiple identifiers being used for the same piece of software.

Attribution for pieces/snippets of code

While DOI and SWH-ID allow citations of full pieces of software/code, there is also the case where a small code snippet or section might be copied into another code. It is common practice to take a few lines of code to solve a piece of a problem from websites such as StackExchange or Code Ranch, but there should still be an attribution if no changes are being made. This can be done effectively with a comment that includes a link to the webpage from which the code was taken (most sites have an option to create a shortened shareable link that is more code friendly).

Publishing open software in peer-reviewed journals

It is also possible to publish open software or a research article detailing the inner workings of that software in peer review journals. A general example is the Journal of Open Source Software; there are also more discipline specific journals such as Astronomy and Computing and Environmental Modeling & Software. The peer review process for some of these journals may include a review of the code itself, some may be focused just on the describing journal article that accompanies it. These publications will also come with a permanent identifier as is customary with most journal articles.

External Requirements

There are various legal considerations to keep in mind with regard to software and code you write. For example, these may be considered intellectual property, and you may wonder who has ownership over it. Generally speaking much of this is dependent on your employment and funding situation at the time you did the work. Your institution may have claim to part or all of the work product, however it is highly variable, and your institutional offices should be contacted to understand this better.

There may also be other institutional, governmental, or other legal policies that may be dependent on your region. Please make sure you understand your locality’s laws and regulations regarding the sharing of research software and follow your institution and funding agency’s requirements (if any) on licensing and intellectual property.

Additional Resources

Code publication Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics - example of a preservation repository that provides peer review When to cite software CiteAs: a resource for finding the correct attribution of a research product

Summary

Here, we reviewed that a software license is a legal binding document, made between the developer and the user of a software, which outlines how that software can be used and distributed. Open software will carry licenses that follow the Open Software Initiative (OSI) definitions: allowing the software to “to be freely used, modified, and shared.” (Open Software Initiative OSI)

We have presented the major categories of licenses that might fall under the open-source definition, and what considerations to take when choosing a specific software and/or license for your software, i.e. 1) what is the intended use of this software?, 2) how others can reuse it? And what are the policies of my institution and local laws regarding open-software use and dissemination?

We have also learned about proper attribution - how to get credit for your work (DOI, archival of code, publishing options), and how to cite others work.

References

Morin, A., Urban, J., & Sliz, P. (2012). A quick guide to software licensing for the scientist-programmer. PLoS Computational Biology, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002598↩︎

Smith et al. (2016). Software Citation Principles. PeerJ Comput. Sci., DOI 10.7717/peerj-cs.86↩︎

Chue Hong, Neil P., Katz, Daniel S., Barker, Michelle, Lamprecht, Anna-Lena, Martinez, Carlos, Psomopoulos, Fotis E., Harrow, Jen, Castro, Leyla Jael, Gruenpeter, Morane, Martinez, Paula Andrea, Honeyman, Tom, Struck, Alessandra, Lee, Allen, Loewe, Axel, van Werkhoven, Ben, Jones, Catherine, Garijo, Daniel, Plomp, Esther, Genova, Francoise, … RDA FAIR4RS WG. (2022). FAIR Principles for Research Software (FAIR4RS Principles) (1.0). https://doi.org/10.15497/RDA00068↩︎