Not an afterthought

Previous lessons have shown the importance and benefits of open science, presented some key stakeholders involved, and discussed the barriers to participation and ways to overcome them. This lesson will guide you in how to start infusing responsible Open Science in your own work, which might be independent, or could be in a research group or lab.

Plan for open science into the design

Practicing responsible Open Science requires organizing your work and research, and your team, if you have one, around open science and planning for it from the inception, even designing the project with open science in mind. There are many resources and tools that make these easy, and indeed doing so will improve efficiency and the value and impact of your work, and help you focus on your research itself. We’ll provide a brief overview in this lesson, but you may wish to explore the later modules in this course too, which cover 🔗 Open Data, Open Results, Open Tools, and Open Software 🔗. Additional resources, and knowledge, may be available at your institution, including in your department or library or among your colleagues. An additional resource is a recent report from the U.S. National Academies “Open Science by Design.”

It is important to discuss responsible Open Science with your research team, lab, group or partners regularly. Much of responsible Open Science may seem to be related to outputs – such as data, software, and publications – but preparing and organizing work for these in advance is critical. It would be hard or impossible to follow leading practices for these at the end of research, in the “afterthought” mode. Responsible Open Science is both a mindset and culture.

Planning for outputs in advance includes: speaking about it and organizing with your research team; deciding which tools to use; thinking about authorship and credit; engaging with relevant stakeholders and research partners, for example, industry, around open science; identifying repositories for software and data; highlighting these approaches in your grant; and much more.

Perks of digital and internet age for responsible Open Science:

The internet has made it very easy to share digital work. The popularization of Open Source computer code and the rise of Open Science has resulted in many outlets for public and free hosting of research and data.One key to open science, and why it is so empowering for 21st century science, is that we can now connect all the participants, stakeholders, and outputs of a research result together so that they are easy to discover.

Here we present a non-exhaustive list of digital platforms and tools used with for open science:

- Digital Persistent identifiers - for objects and researchers (such as doi and ORCID)

- Open Journal System: open source software for managing & publishing scholarly journals

- Electronic notebooks such as Jupyter and R Markdown

- Data repositories: genetic sequence database Genbank, protein data bank (PDB), Dataverse, figshare, Zenodo and for wide search use https://www.re3data.org/ and/or https://datacite.org/

- Softwares/Codes: Zenodo used with Github / mybinder

- Materials: Addgene (for molecular biology)

- Reference management tools: Zotero, Mendeley

- Academic Social networks: Academia.edu, ResearchGate

- Peer Review: Publons, PreView

- Project management: Open Science framework

- Github as a platform for collaborative work on training materials etc

A variety of tools are emerging to help manage open science workflows, and to support global collaboration. These include spaces for project management, such as the Open Science Framework from Center for Open Science, electronic notebooks which help projects organize data, software, and content together; online platforms for creating manuscripts, etc. More information about the open science collaboration and management tools are described in the 🔗Open Tools module🔗.

Now let’s move to the tools and procedures to ensure credit and attribution for our work, and allow its use and reuse in new, powerful ways, using the internet.

Digital persistent identifiers - for objects and researchers

A key to the 📖interoperability📖 is that each piece is assigned a “📖persistent identifier📖” and “📖metadata📖” that provides a secure path and basic information about it in such a way that they can be linked automatically (machine-readable).

How many times have you gone to an old link, only to find the page is no longer there? A persistent identifier is powerful because it is designed to point to the Web resource even if, or when, the URL or domain changes. One very common type of persistent identifier is a “📖digital object identifier” (DOI)📖 that is usually assigned to a digital object (e.g. document) by publishers, preprint servers, data and software repositories. This has allowed automated linking of references across publications, including to citations after a publication.

Case scenarios:

- A researcher writes a script in R that they use to analyze their results and produce a bar chart. They can upload their R code to a repository, and get a DOI for their script, so others can peer-review the code if they wish.

- A member of the public attends a conference online and shares a digital poster and a short talk about their work as a citizen scientist. They deposit their poster and talk slides on to Zenodo, and can share the slides and poster using the DOI URL and receive credit for it.

- A consortium member collaboratively authors a paper summarizing the results of a workshop they attended, alongside other workshop attendees. The journal they publish in automatically assigns a DOI to the paper.

Making your work useful to others:

Discipline- and sector-specific nuances

The above information applies across nearly all scholarly disciplines. There are some discipline or research specific responsible Open Science steps that also apply or for which you should think and learn about:

For some fields of research, 📖pre-registration of hypotheses📖–as a publication–is strongly encouraged and it helps avoid bias and supports the publication of negative results. These are becoming common in behavioral and social sciences and clinical trials. We explored this previously in lesson 2.

If your research involves partnering with industry where some outcomes may be restricted from publication, it is best to discuss and reach agreement in advance on responsible Open Science outputs to avoid complications or misunderstanding at the time of publication. If you have one, consult your institutional legal, knowledge transfer or intellectual support office resources should be consulted to be clear that publication of relevant data and software are acknowledged and supported and that data can be placed in appropriate repositories.

Working with physical samples and tools:

Some disciplines also require or encourage sharing of physical materials such as reagents, cell lines, animal models, and materials and have repositories for these, which will also provide appropriate licenses.

If you are collecting or analyzing physical or biological samples, a permanent identifier system has been developed to help you manage your work, support open science, and enable standard methods for identifying, citing, and locating physical samples and comparing analyses from different labs–the IGSN or International Generic Sample Number. Identifiers can be reserved in advance (before collecting). Additional information is in the Data module

Some disciplines in paleontology and anthropology also require and expect open archiving of precious samples in public museums and/or other means to provide open access (digital casts).

If your research involves field work and sample collection, appropriate permits should be obtained including engagement with local authorities and stakeholders–including them openly in your research has many benefits, as we discussed in Lesson 3.

Work on human data and samples, and other sensitive areas often requires initial external ethical review, e.g. in the US by an Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Summary: think beforehand, design for open science, never as an afterthought.

It is important to think about, discuss, and plan for desired outcomes and processes when you begin your research. Learn about where the best repositories are for your data; discuss credit and authorship for each separate open science output, and start using open science tools to organize your work. Reach out to repositories in your discipline and institution (usually library) for help. Indeed this information in your grants and data management plans will make you more likely to receive funding.

Bonus section: Open Science Skills

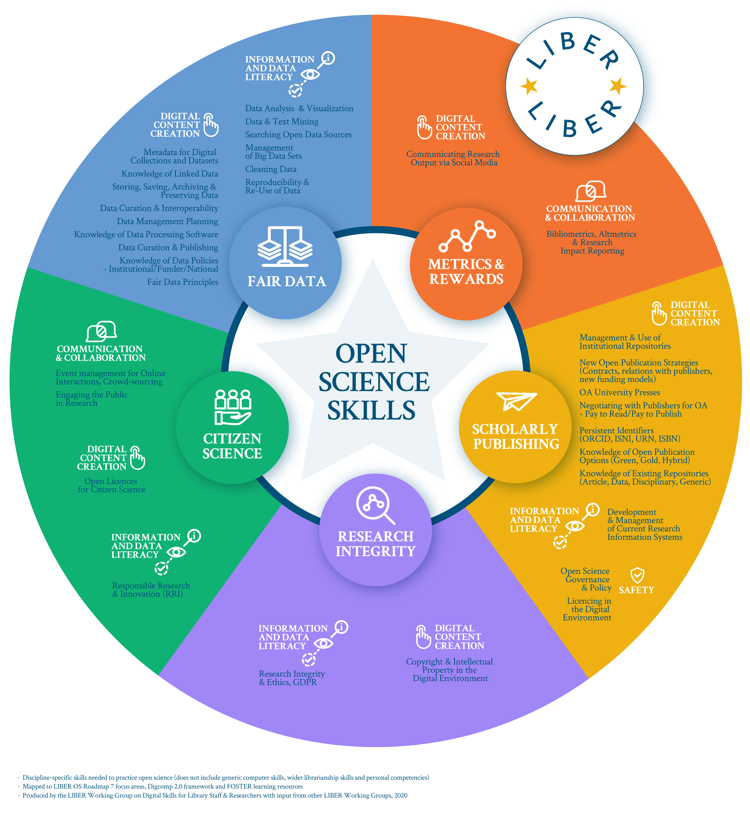

Open science can foster a range of skills, across many domains - the figure below touches on some of the topics you may have learned about so far.

You may have expected to see technical/data science skills, digital content creation, research management, library and information, and publication literacy. Research integrity and ethics are often less straightforward sets of skills, in which researchers may not be trained or aware of.

Each step of responsible Open Science involves considering and thinking about other people - collaborators, contributors, users and consumers of the research outputs. Therefore, communication and interpersonal skills, especially applied to virtual environments, are key.

In this module, we emphasized ethos and ethics of open science, inclusion and accessibility in participation of open science stakeholders, equity (or lack of it) in conducting and sharing science openly. responsible Open Science researchers of the 21st century need to develop their reflective practice, just like practitioners, to enable them to become aware of their own stance towards science or assumptions regarding other stakeholders, aware of the values and worldviews, and provide means to adapt the responsible Open Science practice. (Roedema et al 2022)

Source of the visual

Summary of the module

This module provided a broad overview of the ethos of responsible Open Science, the imperative for scientific and societal challenges and opportunities in the 21st century, and an introduction to how you and your research team can begin to follow leading practices to enable open science. Part of the ethos is to help enable these practices within your team and with your colleagues–that is, you are encouraged and empowered to share what you have learned and help them learn about, be aware of, and practice Responsible Open Source.

In a larger context, many of you will be participating in scholarly efforts, including in peer review, in leadership positions as journals and societies, in organizing meeting sessions, and more. Enabling responsible Open Science is a broader cultural shift in scholarly practices worldwide. In many ways, the recognition, reward and award systems in science are not fully aligned yet with responsible Open Science as this cultural shift is ongoing. You are encouraged to leverage this learning in having conversations to develop this culture broadly.

Here are the six key guidelines to start practicing and supporting open science responsibly:

- Plan for responsible Open Science from the beginning and begin discussions in your group, with colleagues, and your librarian.

- Plan for making data and code open and available in leading repositories and citing it in publications in the reference section. Cite others’ data and software that you make use of.

- Learn about and adopt open science tools

- Develop and foster inclusive workgroups, meeting sessions, and meetings.

- Learn the routes to make your publications open and what your institution supports and funders require; preprints provide an easy and robust route

- Support and inform your colleagues.

Questions/Reflection:

- How can a researcher publish in an open access journal ?

- Predatory journals are very harmful and some early career researchers may not be even familiar with these journals. Describe why they should be not included in responsible Open Science. Also discuss what are the possible ways to restrict and control these journals?

- Why are licenses an integral part of Open Science practice ?

- Can you briefly describe the differences between licence types? When conflicts arise among co-authors about which types of licenses they should choose, how do you discuss and resolve the issue using your knowledge learned from this lesson?

- What are two types of permanent identifiers, and why are they useful?